Top 10 — First-Time Watches of 2020

Creating a Top 10 Films of 2020 list right now seems moot. For me, anyway. There’s just still so much that I haven’t seen yet; I’m not cool enough to get screeners weeks in advance of a film’s premiere, and I am not affluent enough to pay for multiple rentals each month. So, most of the movies I check out I either eventually acquire for free via the public library or as part of a streaming platform’s catalog. Plus, most of what I consume came out before I was even born, so, all things considered, publishing a list of the best pre-2020 movies that I watched for the first time makes tons more sense.

I’m both proud and embarrassed to report that I watched, ohhh, a few hundred movies in 2020… 624, to be precise (according to Letterboxd). But narrowing that figure down to merely ten titles was not as difficult as I expected it to be—because every picture included below is on a god-level tier, in my opinion. And several of them possess elements of queerness, too.

There’s no traditional horror here, however, which is kinda surprising, but then again maybe not. Thanks to my almost-three decades of moviegoing, I’d already seen a plethora of the major horror titles by 2020—and I’m not counting rewatches. I plan to remedy this absence of scary movies by watching more deep cuts in 2021. Thus, next year will be about finding those hidden gems. Let’s consider that my New Year’s resolution!

(Warning: at the top of 2020, I purchased a year-long subscription to the Criterion Channel. So, sorry in advance—I’m about to get high brow.)

10. Rocco and His Brothers (1960)

Italy

dir. Luchino Visconti

At some point while watching this movie, I thought, I bet Tennessee Williams loved this.

I mean, it’s like a homoerotic John Steinbeck novel on screen: The domestic politics. The epic scale. The men! The romance. The toxicity. The textured melodrama. The men! The violence. The passion. The intensity. The men!

I’m going to admit something here… I seldom finish 2+ hour movies in one sitting—just because I’m antsy, not because I think movies should always be short. Rocco and His Brothers is a 179-minute family drama, but, rest assured, once I pressed play I sopped up every second until it was over. If this movie came out today, folks on the internet would be griping that it should have been a miniseries. But I’m here to tell those hypothetical idiots to shut up.

9. The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972)

West Germany

dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Wigs, wigs, wigs! Fassbinder is going to be my next director deep-dive, because this film is everything. It’s German gay candy. I mean, I don’t even drink gin, but this movie sure did make me want to start.

The three women at the forefront—Margit Carstensen, Irm Hermann, and Hanna Schygulla—are all fabulous. If this film came out today, the homos of the so-called #FilmTwitter would definitely be debating who the MVP is (also who’s leading and who’s supporting—kill me), and even though there is not an objectively wrong answer, the correct answer is technically cinematographer Michael Ballhaus. There would also be a group shouting that it “would work better as a stage play,” and to those hypothetical fools I say get a new line.

This year I also watched for the first time Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, which is amazing and undoubtedly the more critically revered endeavor in his oeuvre, but The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant is simply more my tempo, so that’s why I’m choosing to include it instead in this subjective list reflecting my personal taste… Furthermore, I’m pretty sure without Petra we wouldn’t have The Duke of Burgundy. So there, nerds.

8. Beau Travail (1999)

France

dir. Claire Denis

I’ve never really had a desire to enlist in the armed services, but goddamn did this movie make me rethink my life choices.

So, there’s a scene in Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again where Christine Baranski takes one look at a foxy Andy Garcia and utters, “Be still, my beating vagina.” And, well, I felt that several times while watching Beau Travail. Only, you know, about my, you know, instead of a, you know…

Look, only women should direct movies about hyper-masculinity. Because only they seem to understand how truly ridiculous (and queer) it all can be. Maybe it has something to do with being brought up in a patriarchal world that generally treats women as second-class citizens, but what do I know?

7. The Ascent (1977)

USSR

dir. Larisa Shepitko

Speaking of women directing movies about men… Here’s a film that was right up my existential alley. The Ascent is about a pair of men so trapped by their dire circumstances that they have nowhere else to go but to the very depths of their own souls. [chef’s kiss]

“Grim” and “bleak” are perhaps my two favorite tones, and Shepitko demonstrates that she is a maestro of both. Visually, she fully understands how ominous the color white is—how hostile it is, how it represents the nearness of death, and how well it evokes feelings of hopelessness; snowy landscapes have seldom ever been so menacing. This film also features some icy stares that are so piercing in nature that your discomfort will compel you to break eye contact with the actor—but you won’t be able to.

Now, I’m not a huge fan of war movies. The ones I tend to find engrossing, though, are the sort that focus more so on the psychological tolls of warfare… I felt so drained when The Ascent ended that I truly had to wonder if Andrei Tarkovsky is really the best Soviet director, because fuuuuuck.

6. Make Way for Tomorrow (1937)

USA

dir. Leo McCarey

Dev. A. Sta. Ting. But in a completely different way!

Leo McCarey won the Best Director prize at the Academy Awards of 1937, although not for making Make Way for Tomorrow. You see, his screwball comedy The Awful Truth, which came out the same year, was much more of a crowd-pleaser and boasted a couple of fabulous star performances. So it’s clear why AMPAS folks favored that one. But McCarey disagreed. When he accepted his Oscar, he reportedly told the members of the Academy that they had recognized him for the wrong film. A bold claim. And one I support.

Make Way for Tomorrow is more solemn and heartrending. It features stunning acting as well, albeit of a totally different variety. McCarey fought to fill his cast with the strongest character actors of the day, because he wanted the audience to see real people on screen, not glamours celebrities. And, boy, was he right to do so. Because when the waterworks hit, they hit hard… The Awful Truth is great, too, don’t get me wrong. But it’s hard to deny the emotional wallop that is Make Way for Tomorrow.

5. Tongues Untied (1989)

USA

dir. Marlon Riggs

It had been a while since I’d last found myself so enraptured by a film. With just a 55-minute runtime, Marlon Riggs manages to cover a whole hell of a lot: HIV/AIDS, queer bashing, white gay racism and privilege, Black homophobia, the struggle of being a double-other, the language of snapping, and so much more.

My words could never do this singular work of art justice… Tongues Untied is quite literally poetry as cinema. It’s somewhat miraculous that PBS funded and broadcasted this genius, groundbreaking experiment in documentary storytelling in the age of talking head nonfiction filmmaking. Tax dollars well spent, if you ask me.

In other words, quit fuckin’ around and seek this out right now.

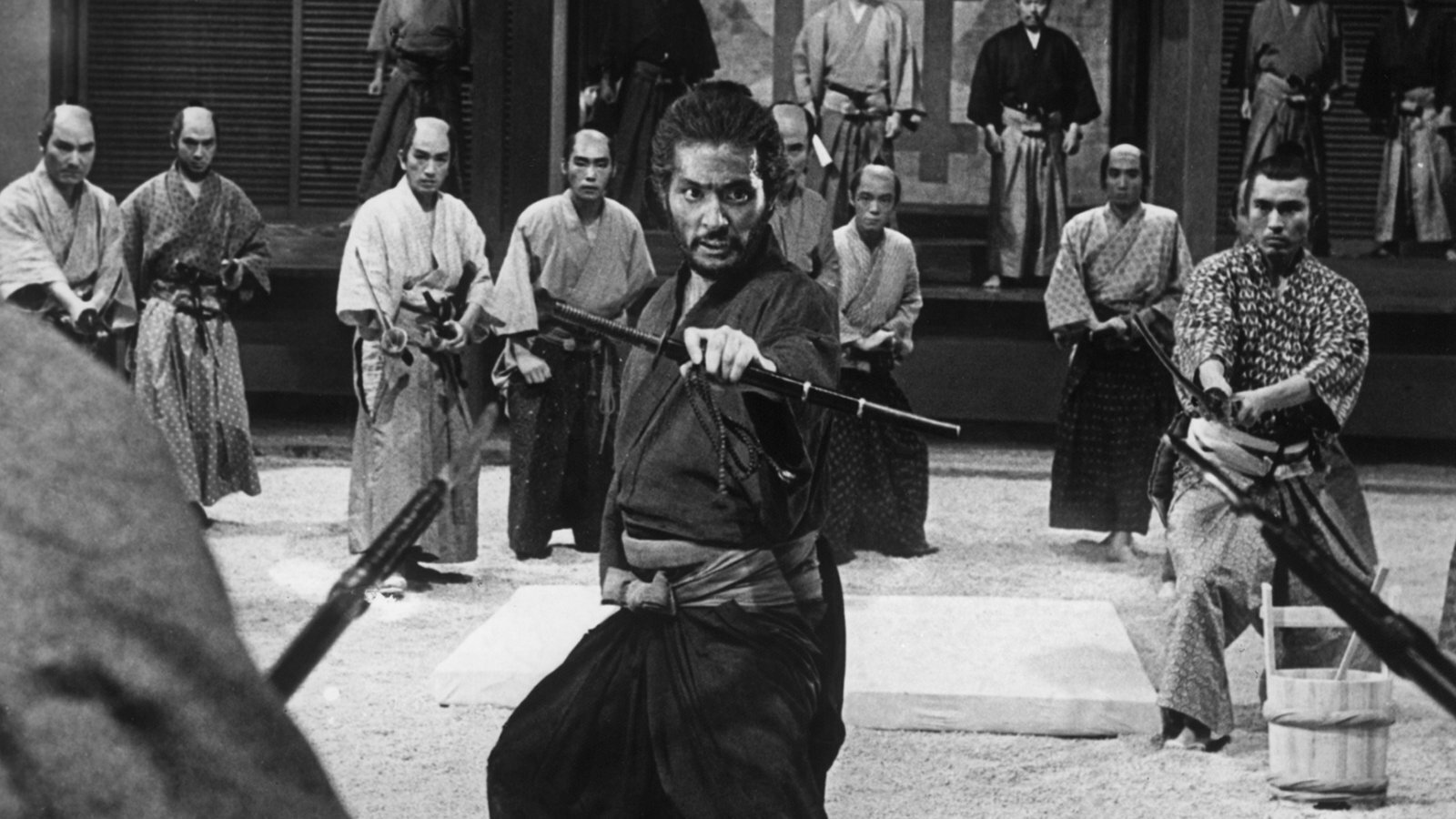

4. Harakiri (1962)

Japan

dir. Masaki Kobayashi

I watched Harakiri because it currently sits at the #4 notch on Letterboxd’s user ratings-driven Top 250 Narrative Feature Films list. (The fact that I also have it at #4 is purely coincidental, or it’s some type of Freudian weirdness—you decide.) And having now seen it, I fully understand why cinephiles love this film.

First of all, I’m not sure what took me so long to get around to Harakiri considering how much I admire Kwaidan, Kobayashi’s subsequent picture. Secondly, like Kwaidan, Kobayashi spins this yarn with the utmost confidence. His grasp of visual storytelling is astounding. One of the things that makes Harakiri in particular so impressive is its bold and elegant plot structure, which works largely due to the meticulousness of its director. Quite simply, I’m still in awe.

Oh, and I shan’t forget Tatsuya Nakadai’s deft performance!

Son of a bitch. This means I have to watch The Human Condition trilogy now, doesn’t it? Ugh, yes, yes it does… I’m grumbling at the moment, but just watch my petite fuzzy ass adore each of the three 3+ hour installments. Damn you, Masaki Kobayashi. Damn you and your brilliance, you bastard.

3. Jane B. par Agnès V. (1988)

France

dir. Agnès Varda

Agnès Varda is the director whose work I watched the most in 2020. I consumed eighteen of her films—narrative features, documentary features, narrative shorts, documentary shorts—and Jane B. par Agnès V. is by far my favorite of the ones I experienced for the first time.

Throughout her career, Varda played with the fabric of film, more often than most directors perhaps. I love how she’d rip cinema apart at the seams then re-sew it to fit her needs. Each of her projects is a vibrant tapestry in its own rite, and this endeavor in particular is a fantastical documentary that marvelously interweaves the ideas of life and art, time and death, fame and craftsmanship, performer and audience, et cetera, et cetera.

In another Varda documentary (I think it’s The Gleaners and I), she revealed her fondness for soft focus; she found beauty in slightly blurred lines. And that notion is conceptually on display here. Varda does not seem interested in focusing on any one theme. She drifts from thought to thought as if in a daydream, and yet it all somehow blends; that’s her ingenuity.

I know it may sound counterintuitive on paper, but if the awards bodies of the day had felt so inclined to do something unconventional and nominate a documentary in the Best Actress and Best Production Design categories, the merits of Jane B. par Agnès V. would have provided a splendid opportunity to do so.

2. A Matter of Life and Death (1946)

UK

dirs. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

“How?!” Seriously. “How?!” That’s my question for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Because how on earth did they pull this off in 1946?!

Everyone always cites The Red Shoes and Black Narcissus as Powell and Pressburger’s masterpieces—and those two pictures positively are masterpieces—but I’m truly baffled as to why A Matter of Life and Death is not as regularly lauded. It is pure cinema. It’s the definition of sublime.

This is what technicolor was made for. The pigments are mesmerizing; every rich hue is a little slice of heaven. Having a fearless DP like Jack Cardiff, who gallantly painted with every gel and gobo in his toolkit, helps in that regard. And the black and white cinematography—because of course this movie utilizes both—is just as striking. The Archers really knew how to shoot so that each of their film’s magnificent set pieces could shine. That escalator, for example. I’m still not over it.

I don’t often leave a movie moved, but this movie moved me. It made me feel so… alive. Which is a feat for my depressed woolly ass.

1. Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

Belgium

dir. Chantal Akerman

This movie should not work. It simply should not work. A 202-minute long film about a woman doing mundane household chores should not be this gripping. And yet. And fucking yet… It absolutely is. I don’t get how it works, but it works, and there’s only one rational explanation.

Sorcery.

Chantal Akerman is a filmmaking mastermind who hypnotized me for more than three hours. She’s downright diabolical… To circle back for a second, remember earlier when I mentioned how I have a wee problem sitting still for more than a couple hours at a time? Well, here is another case where once I was in it, I was in it. Jeanne Dielman’s life was an open book, and I couldn’t stop reading between the lines.

Look, although Jeanne Dielman is the film that floored me more than any other in 2020, I would not advise everybody to watch it. In fact, there are just a handful of people in my life to whom I’d recommend this film. Most people I know wouldn’t finish it even if they tried, sadly. And that’s okay, I guess.

No work of art is for everyone, especially when it comes to the challenging stuff. And Jeanne Dielman is about as challenging it gets. It demands a lot from its viewers, including a solid chunk of time. But it also requires us to witness the excruciating abject monotony of being an unthanked housewife, to experience for ourselves how the prison of routine eats the soul.

Come to think of it, what if Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is actually a covert horror movie?